Art and Activism: 50 Years of Africana Studies at KU

February 1–May 16, 2021

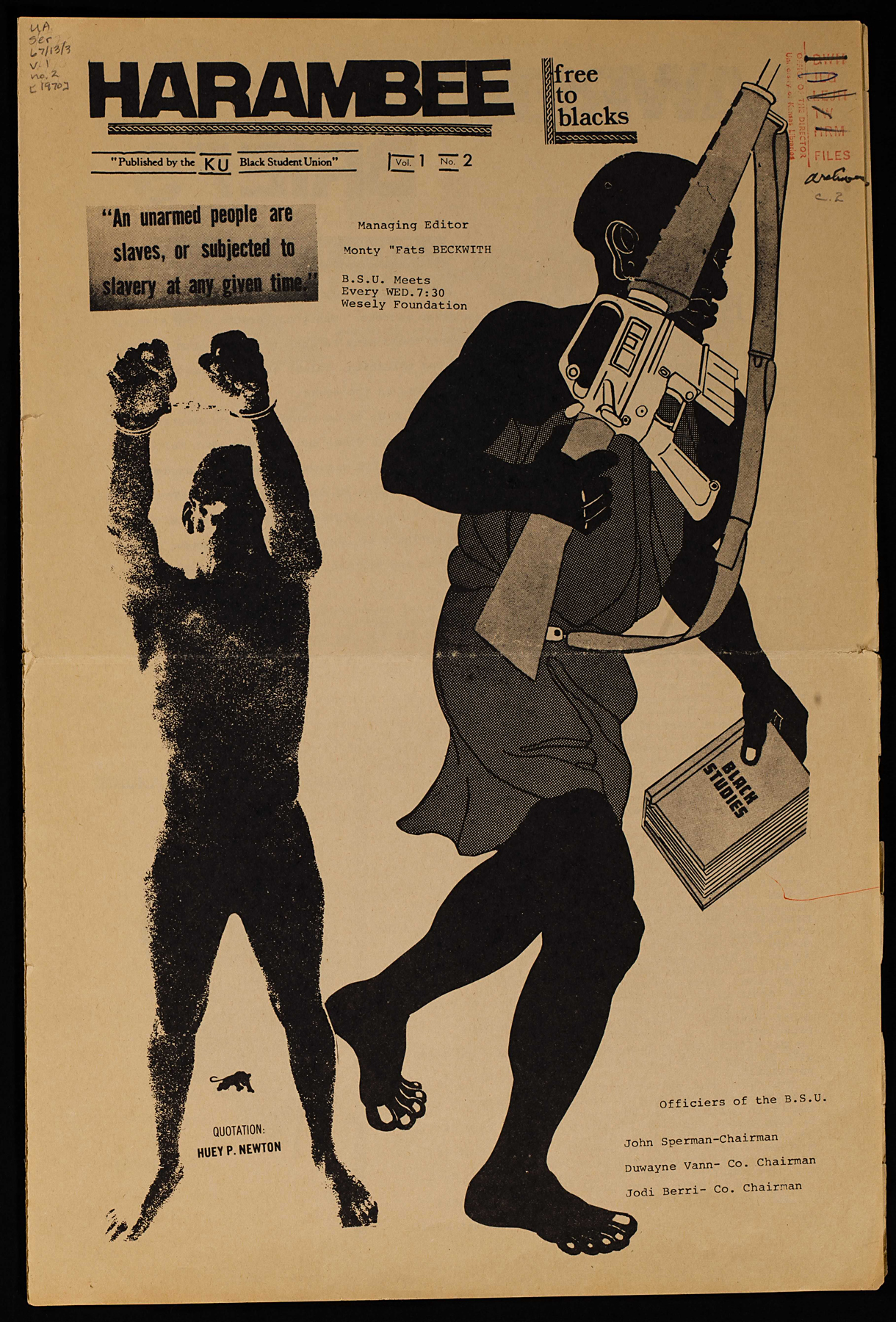

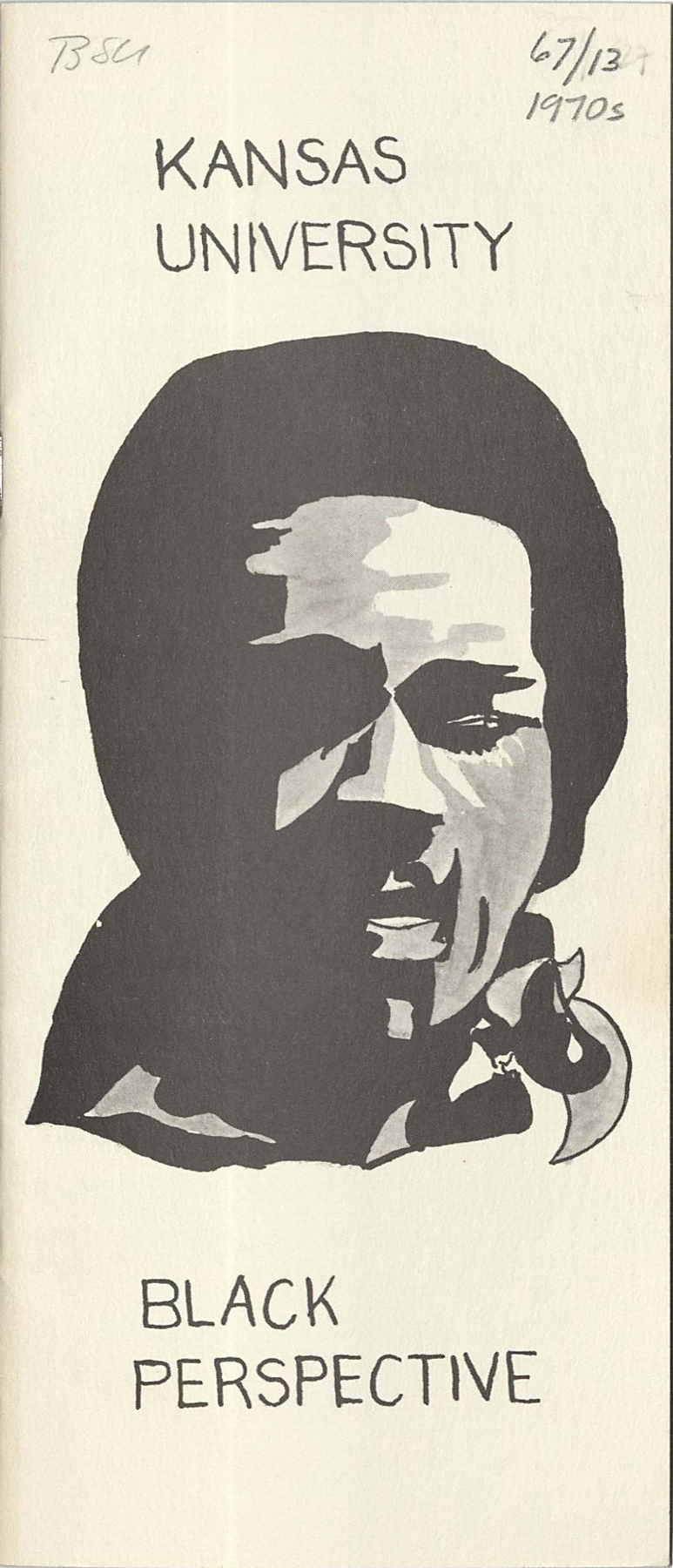

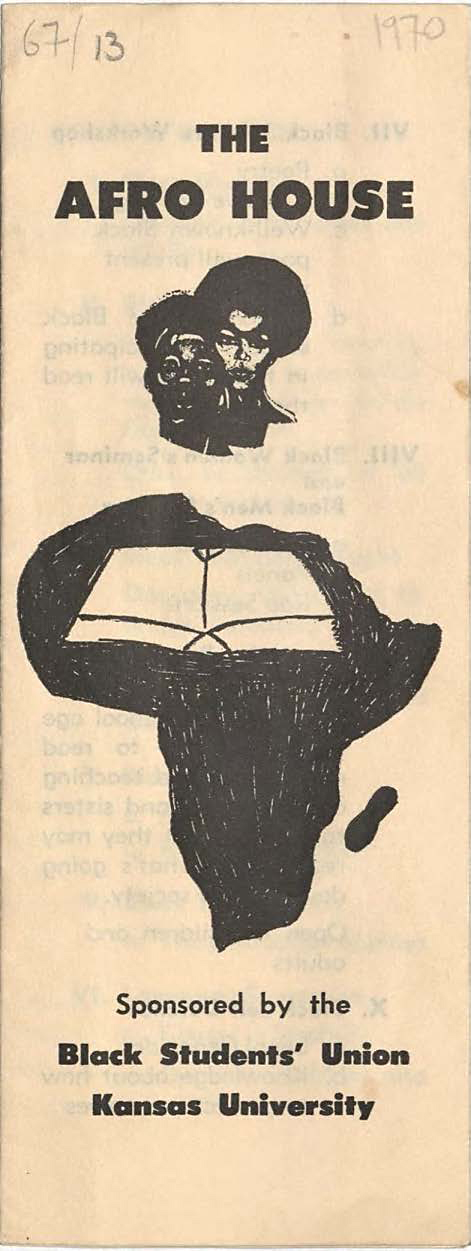

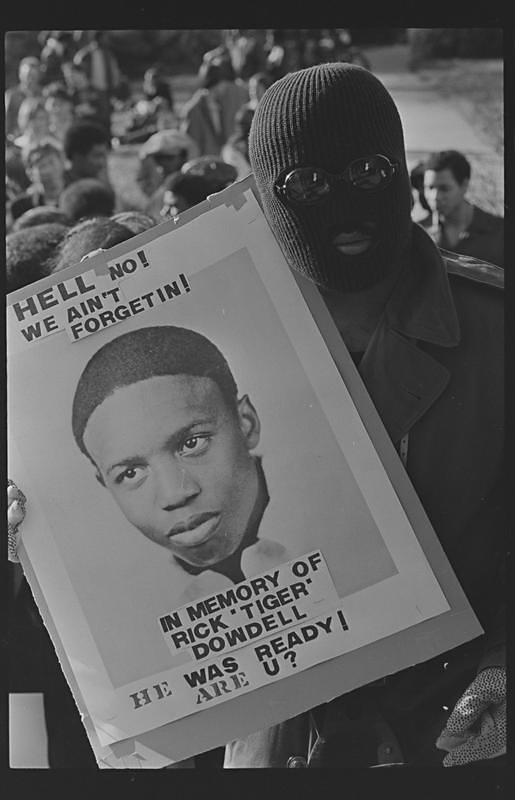

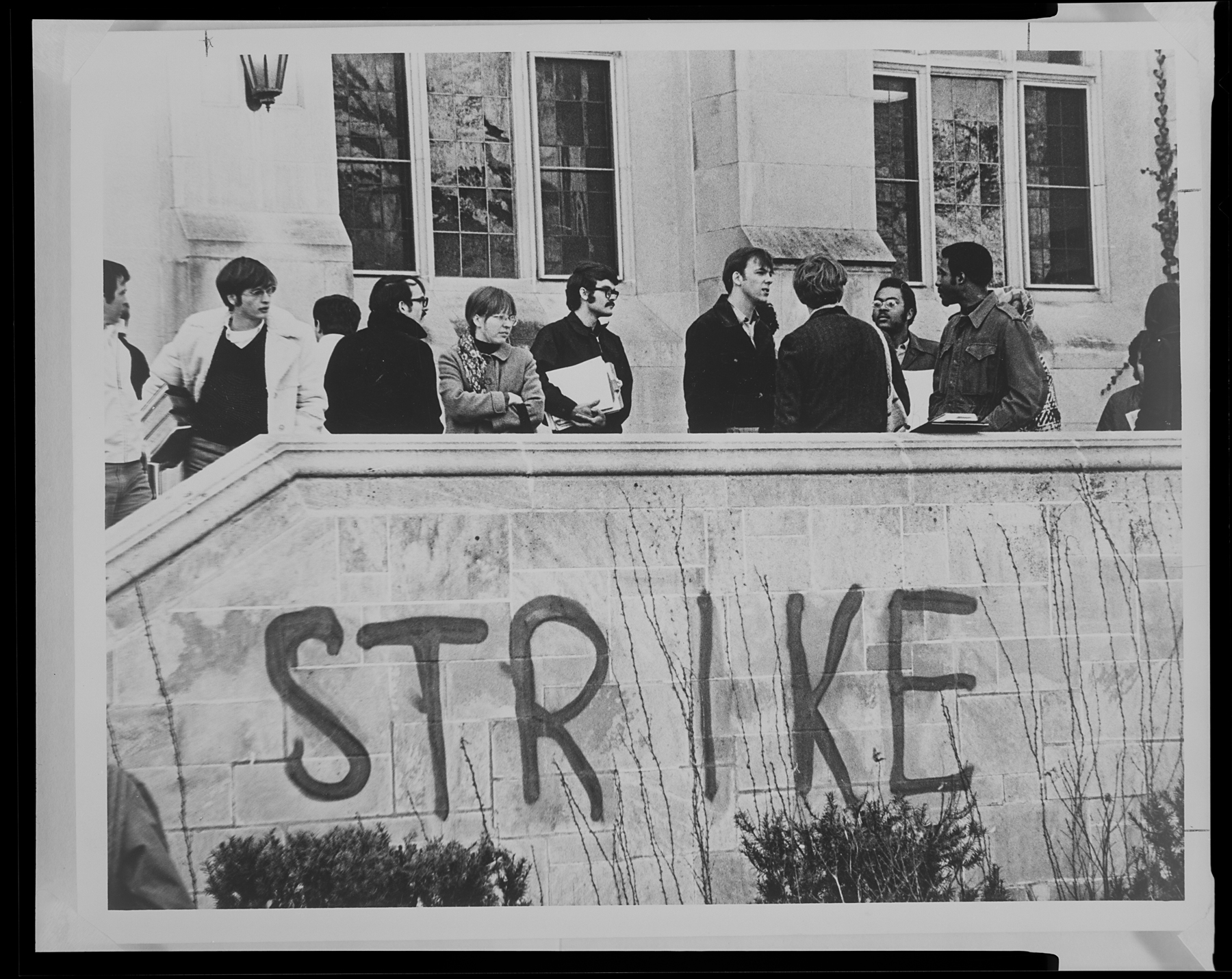

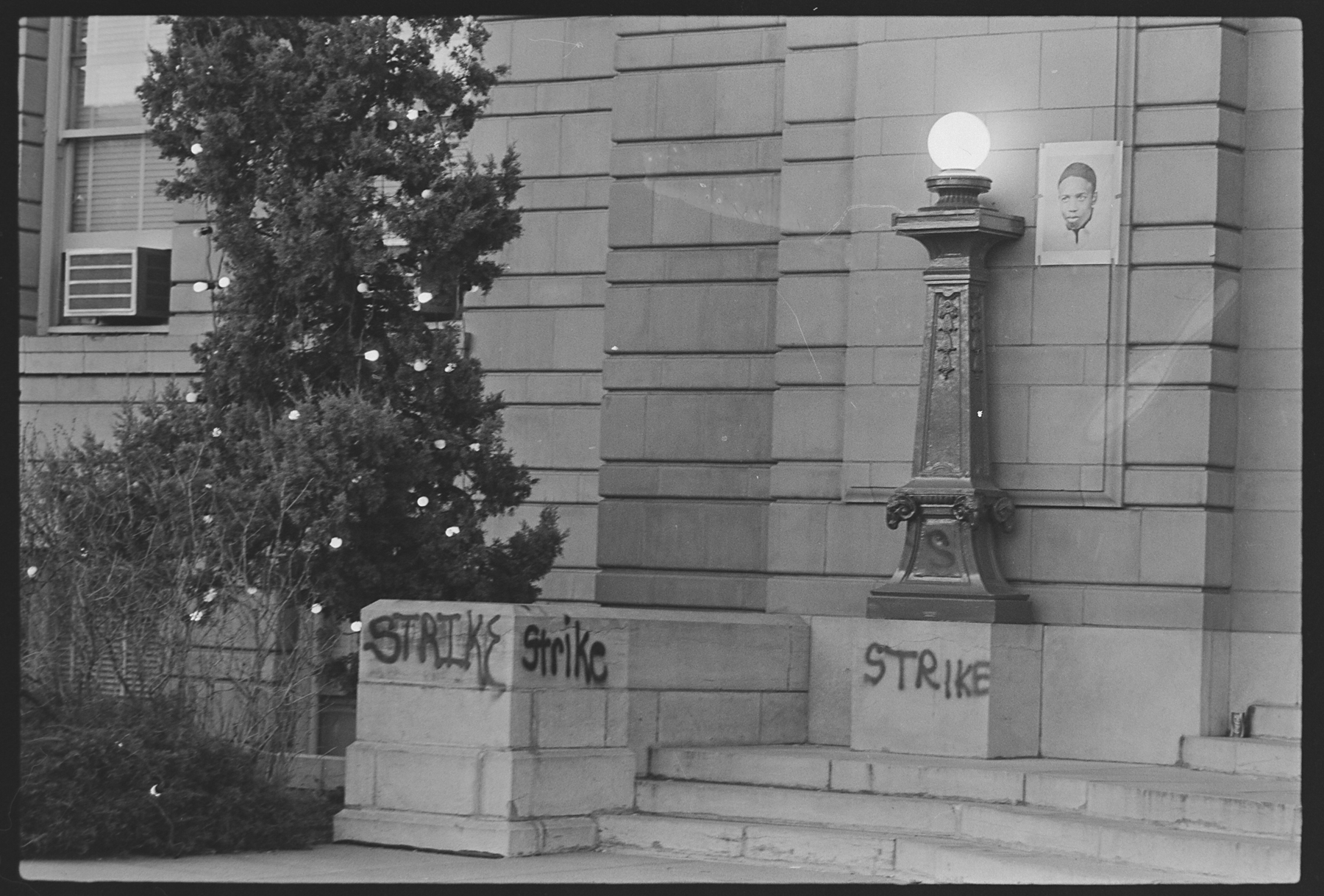

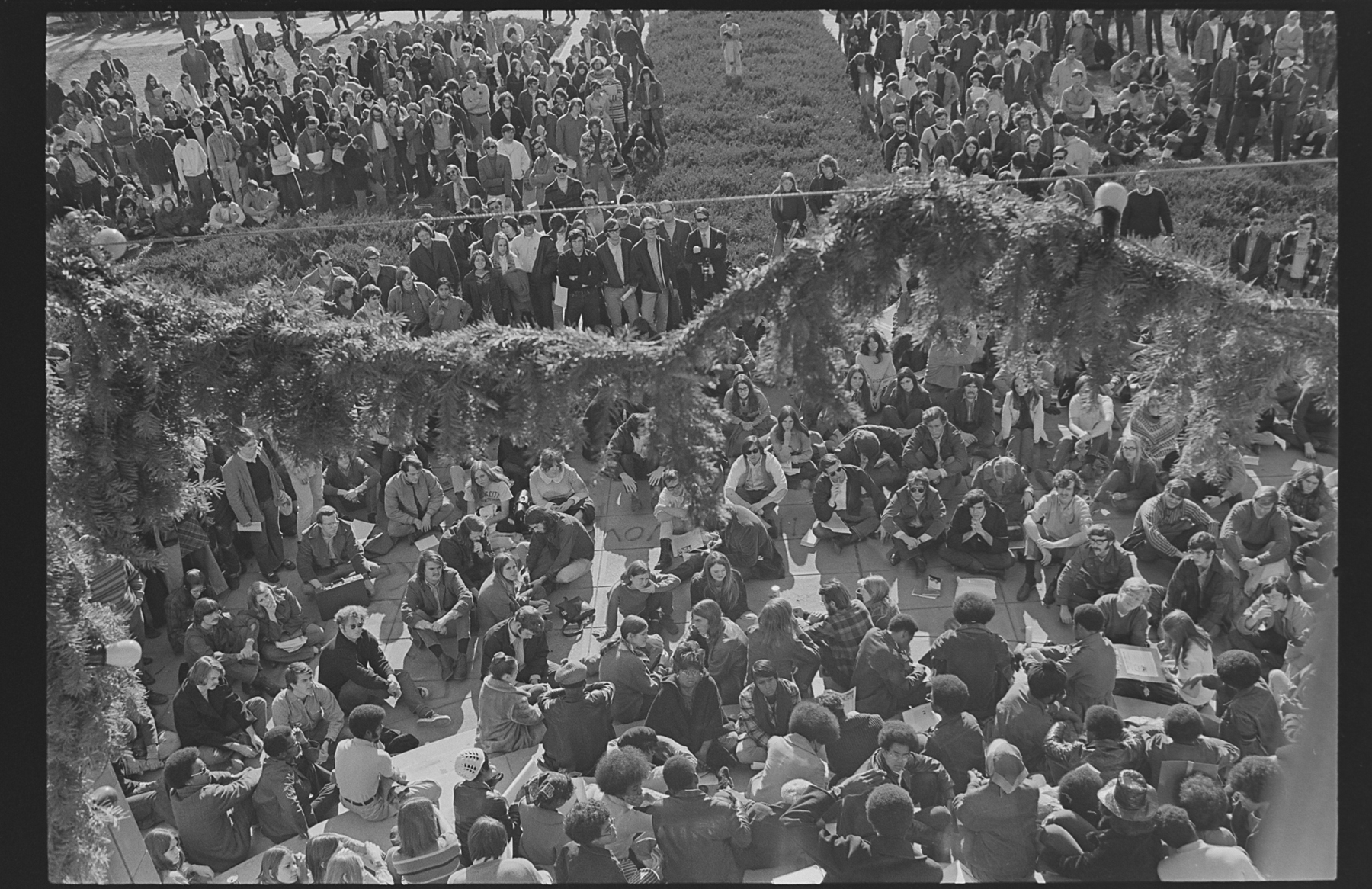

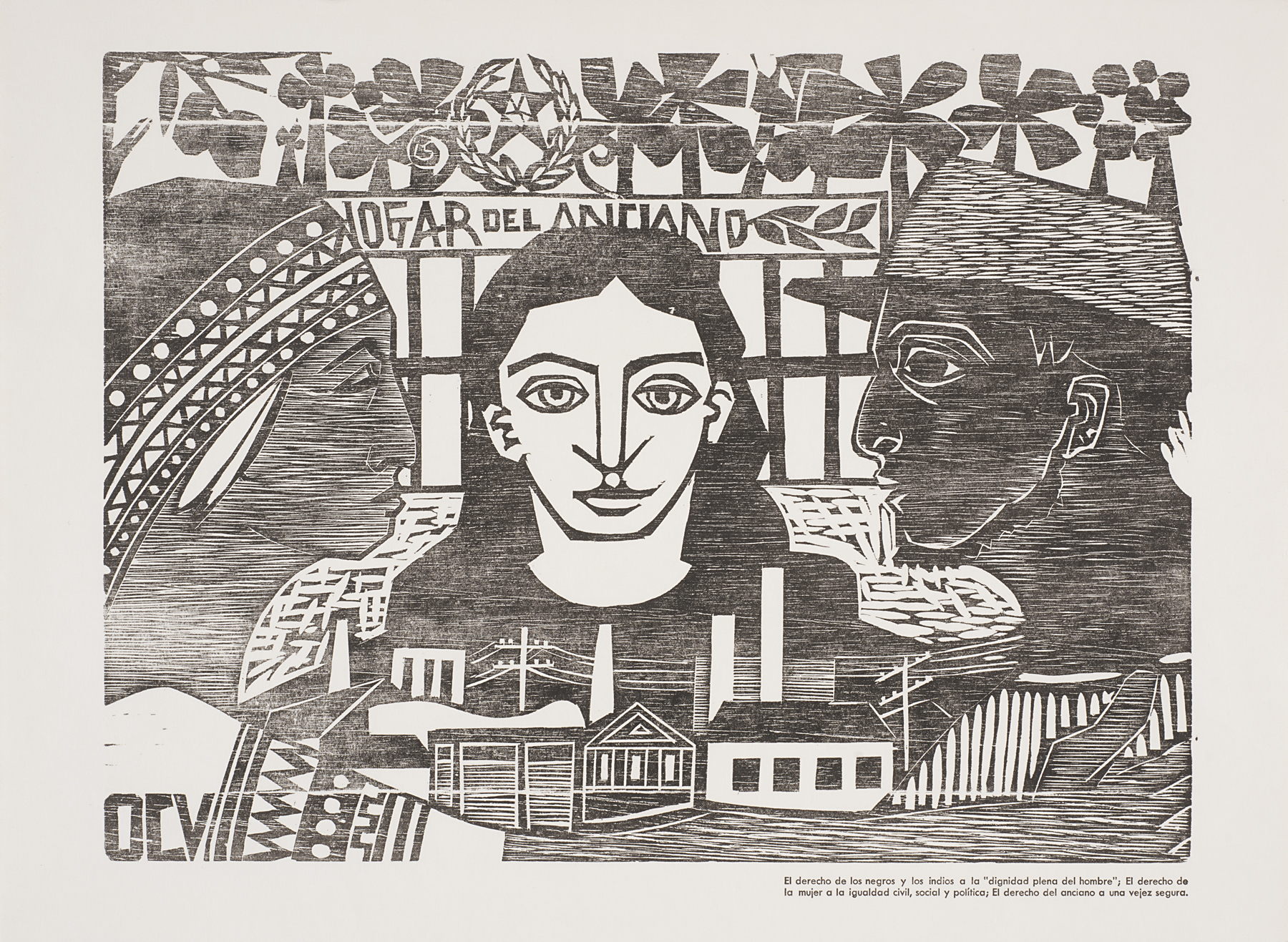

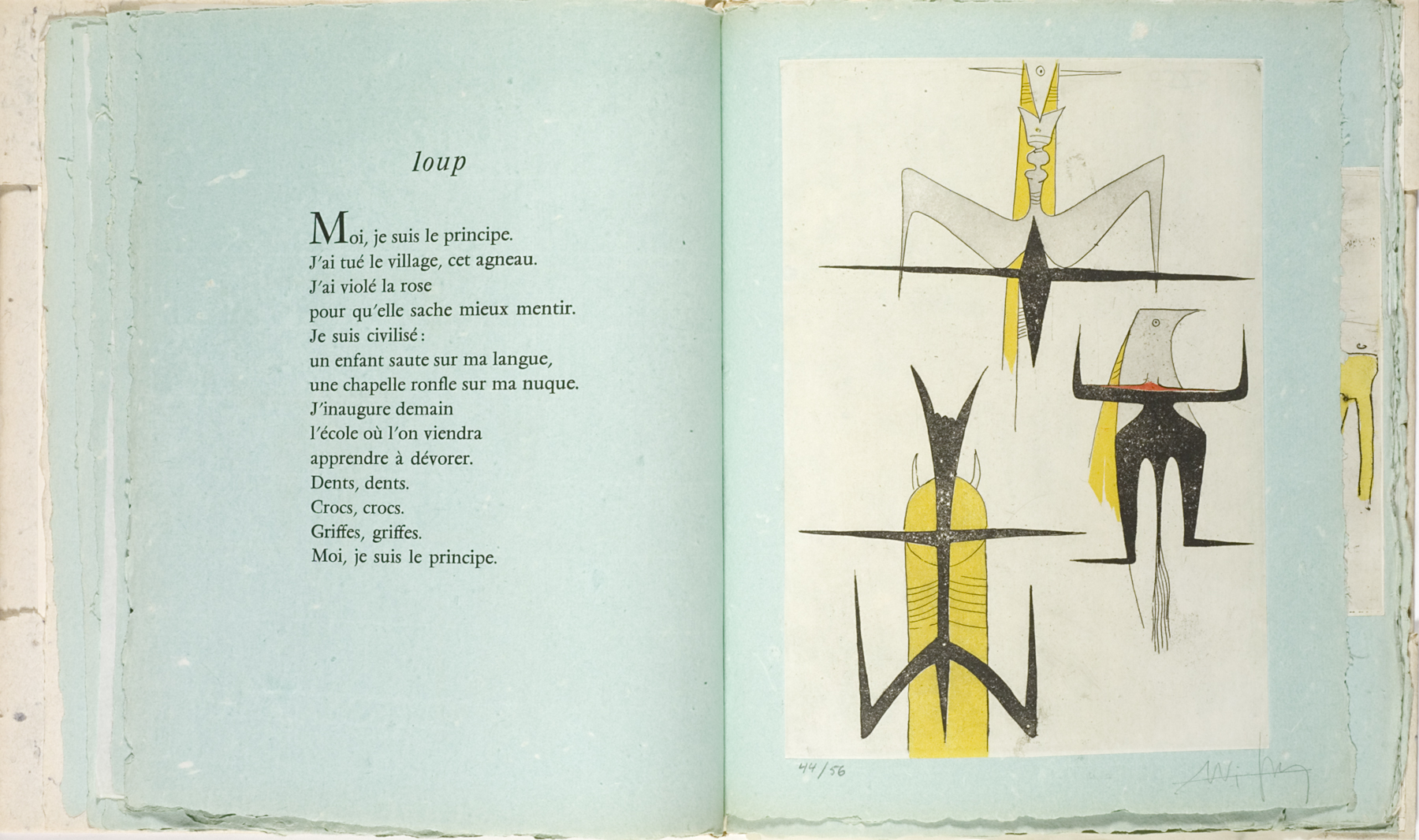

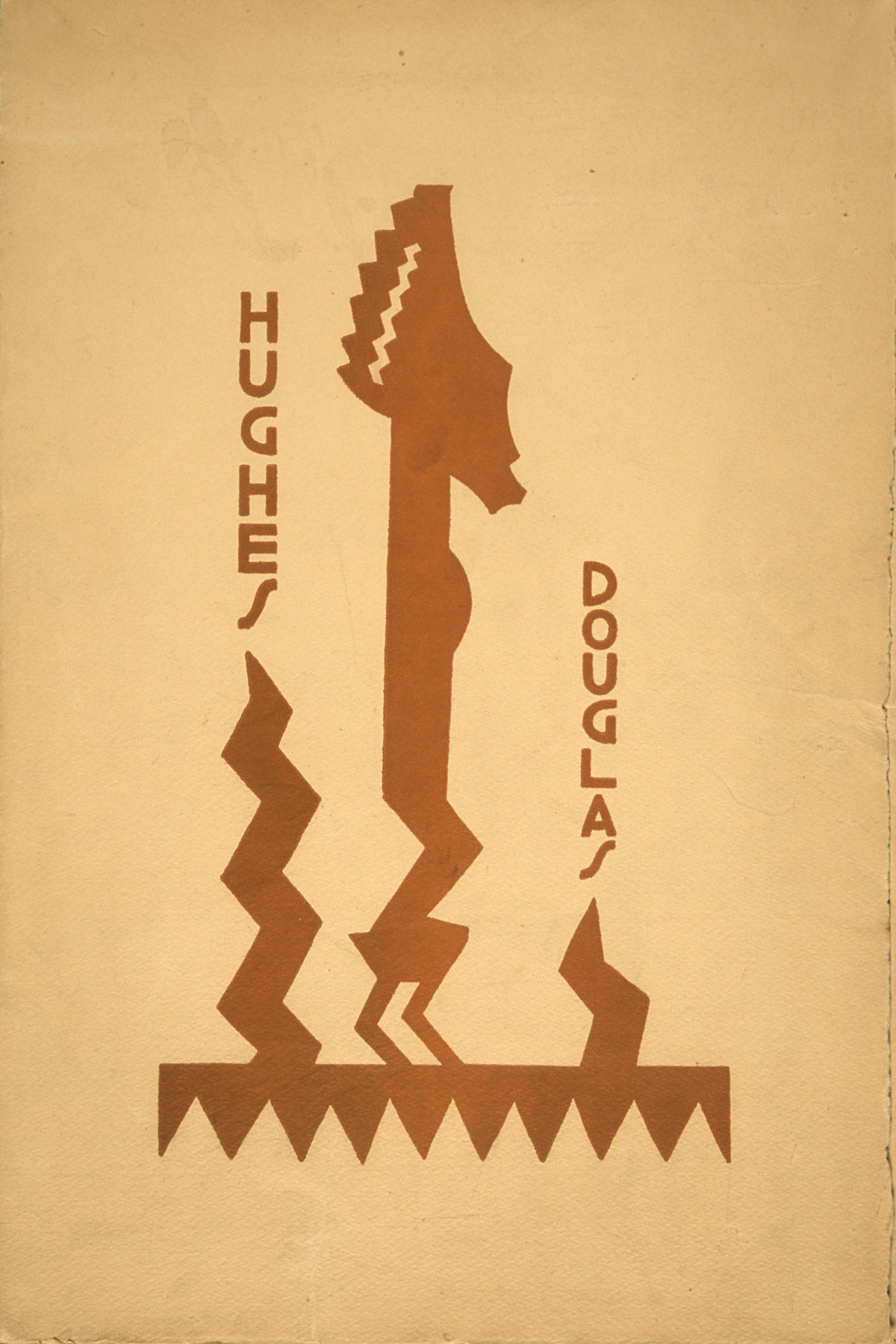

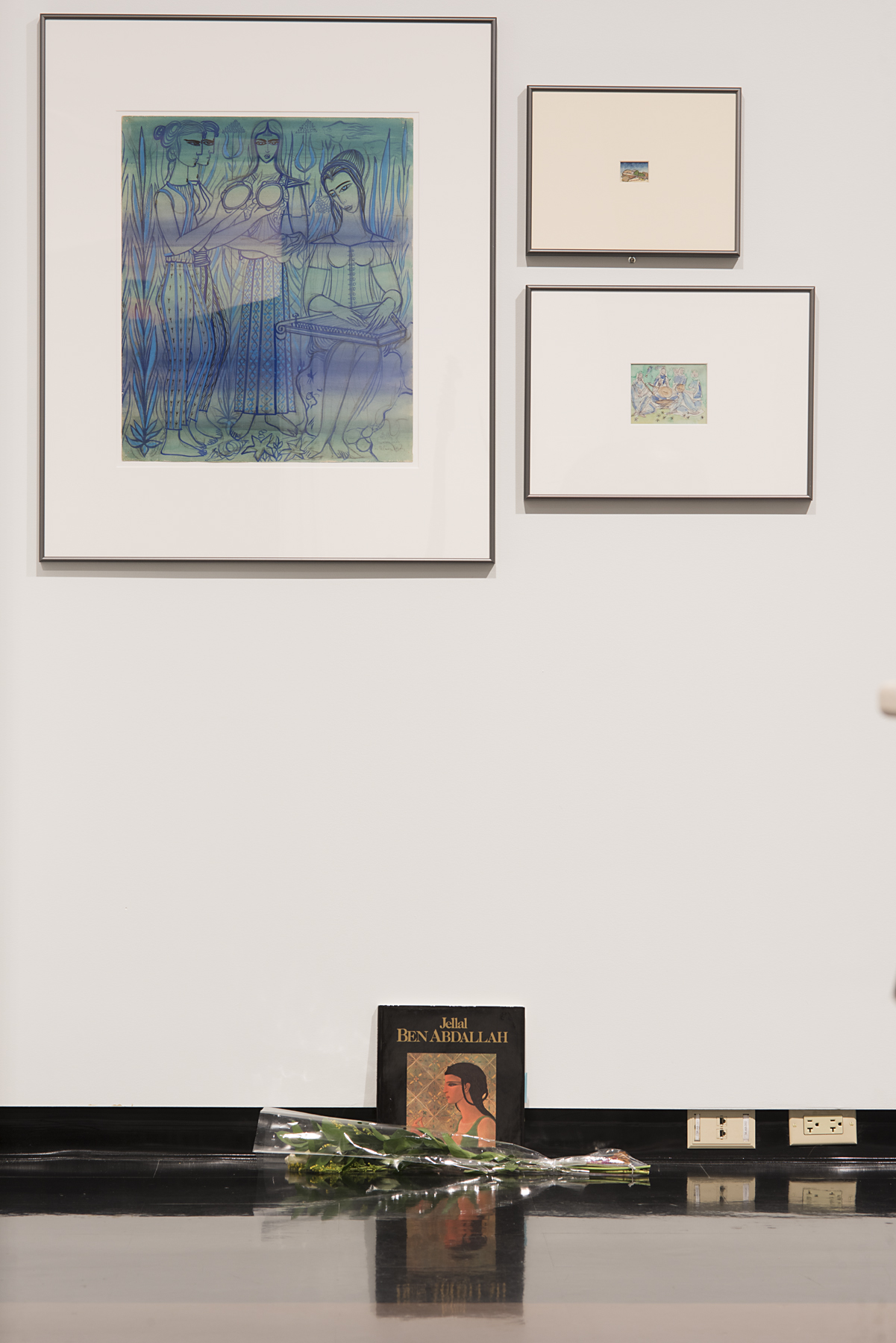

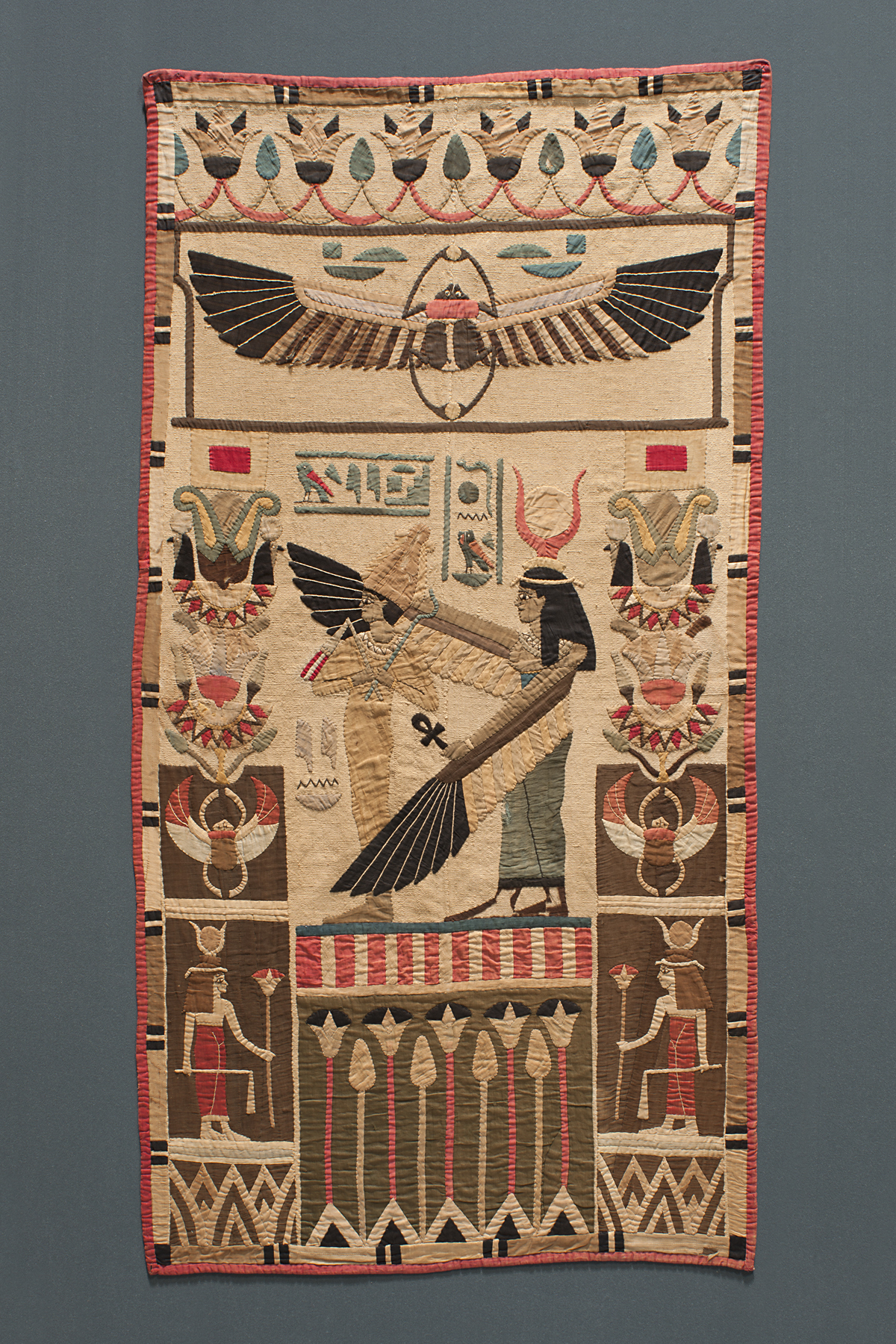

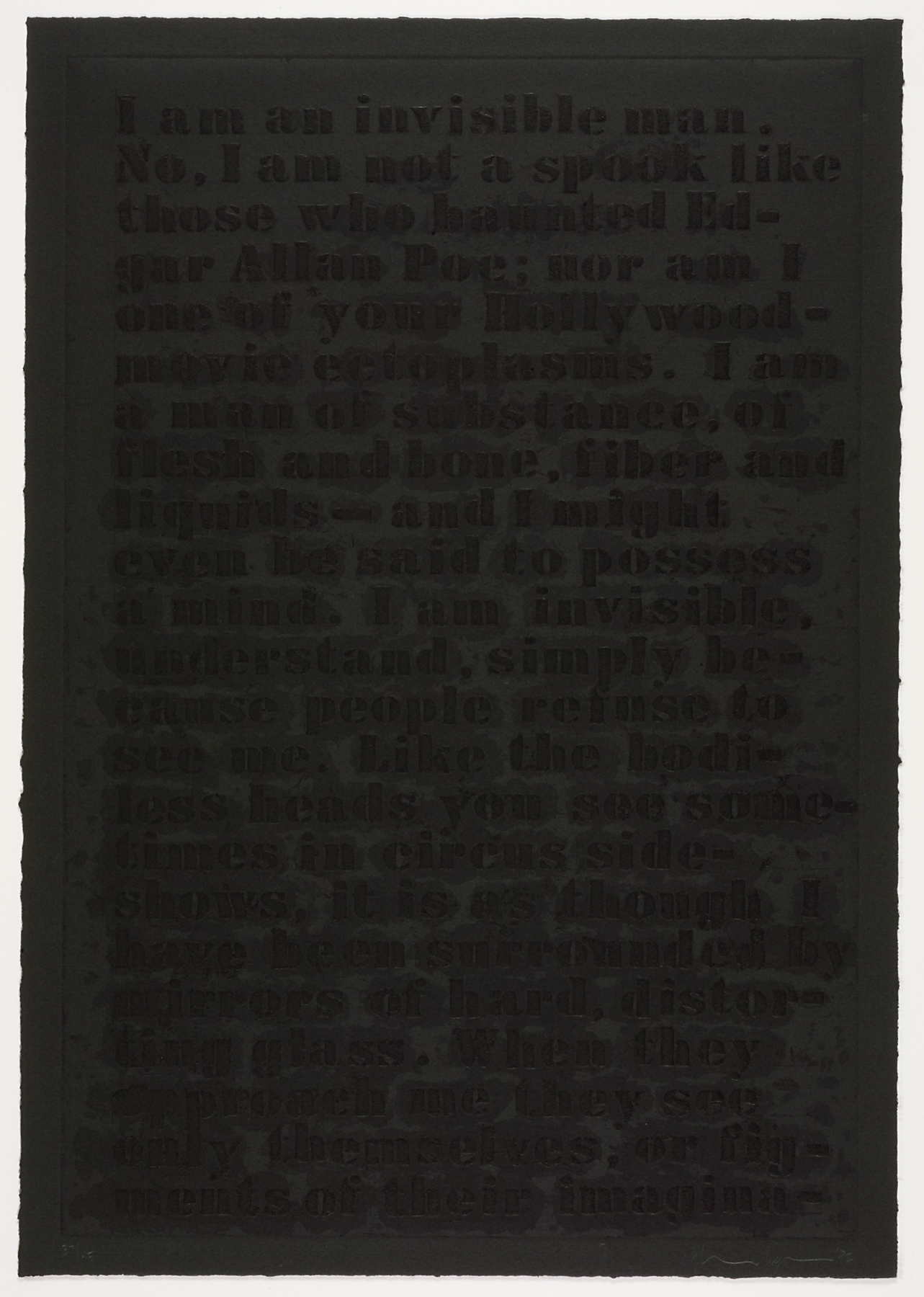

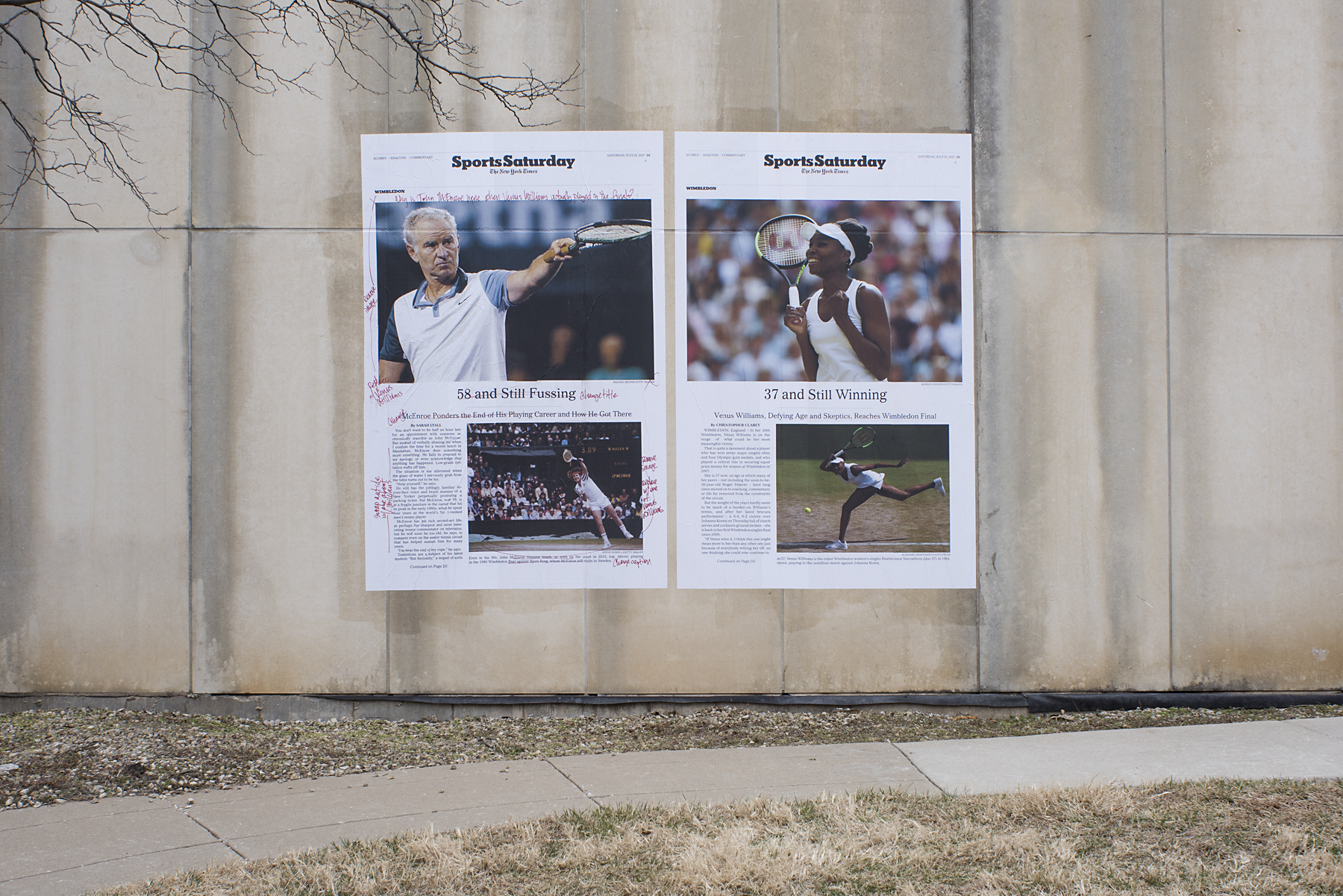

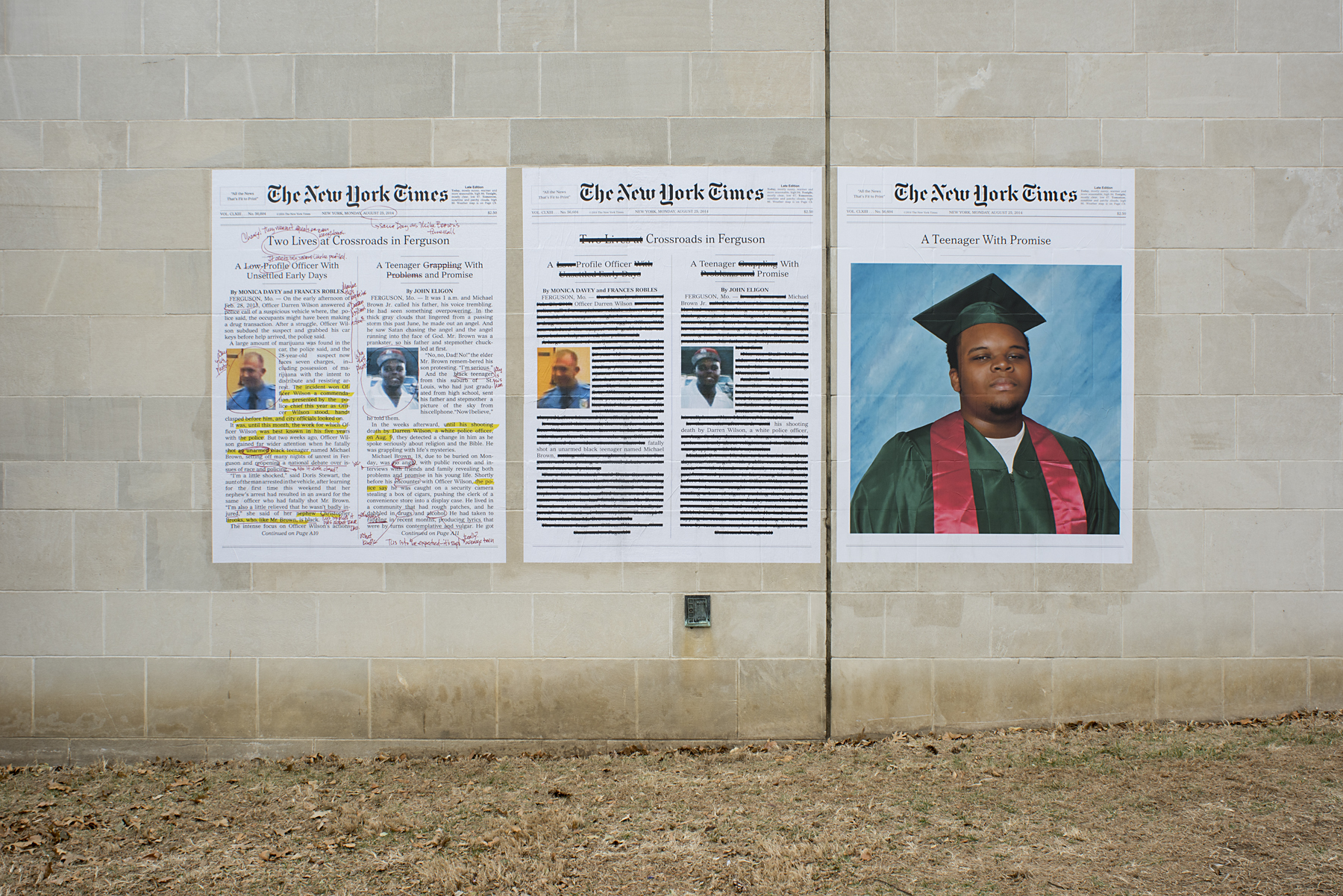

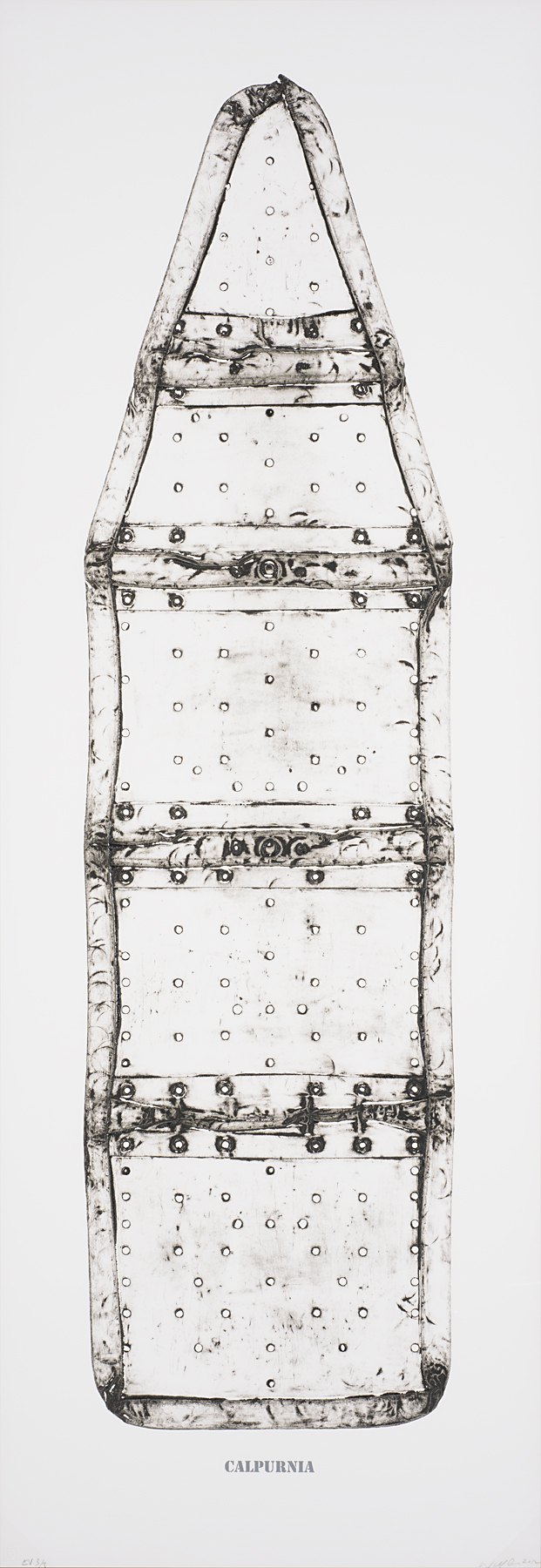

The Department of African and African-American Studies (AAAS) commemorates its 50th year at the University of Kansas (1970–2020). This virtual exhibition depicts the origin of Black Studies on campus and the role of art in the intellectual and activist work of students, faculty, and communities. How does art engage with the long histories of social and political struggle and thought underlying Africana Studies? How are these histories felt and made visible to wider publics through artistic and curatorial practice and outreach? This exhibition chronicles the relationship between AAAS and the Spencer Museum of Art. It explores the context of broader social movements linking Africa and African Diasporas in the Americas and the enduring demand for curricular and structural change at KU. The exhibition is divided in four thematic groups related to the ongoing story of Africana Studies at KU: Origins, Students, Faculty, and Community.

February 1–May 16, 2021

The Department of African and African-American Studies (AAAS) commemorates its 50th year at the University of Kansas (1970–2020). This virtual exhibition depicts the origin of Black Studies on campus and the role of art in the intellectual and activist work of students, faculty, and communities. How does art engage with the long histories of social and political struggle and thought underlying Africana Studies? How are these histories felt and made visible to wider publics through artistic and curatorial practice and outreach? This exhibition chronicles the relationship between AAAS and the Spencer Museum of Art. It explores the context of broader social movements linking Africa and African Diasporas in the Americas and the enduring demand for curricular and structural change at KU. The exhibition is divided in four thematic groups related to the ongoing story of Africana Studies at KU: Origins, Students, Faculty, and Community.